Covid-19 Could Be Eating Your Neurons

How Covid-19 fulfils the Bradford Hill criteria for causation and raises your lifetime risk of dementia from 1% to 1.5%.

This article was originally published at Microbial Instincts on June 10 2024.

As a researcher who has published papers and written articles about the overlooked role of viruses in brain health, I was delighted yet concerned when The Lancet Neurology, a top-tier journal, recently published a viewpoint article, “SARS-CoV-2 infection as a cause of neurodegeneration,” by Bonherry et al. from Europe and Australia.

This article solidifies a vital message that experts in the field have tried to convey to mainstream medicine: Infectious diseases, including the relatively novel Covid-19, are not merely short-term sicknesses; they add to the overall infection burden one faces throughout life. The higher the infection burden, the greater the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

Bonherry et al. present several crucial arguments for the causative role of Covid-19 in neurodegenerative diseases, which I find too important not to write about and share with the broader audience (you all).

Risk factors: An overview

Bonherry et al. first acknowledged that neurodegenerative diseases like dementia are influenced by both genetic and environmental risk factors, of which the latter is modifiable — something we can control.

According to The Lancet Commission in 2020, modifiable risk factors of dementia include low education and social contact, smoking, physical inactivity, brain injury, and others. They also acknowledged the growing significance of infections as a risk factor for dementia.

The Lancet Commission addresses critical global health issues by commissioning a panel of experts to conduct comprehensive reviews and derive evidence-based recommendations. One global health issue is dementia, a disease that robs a person of their memories and sense of self. Every 3 seconds, someone in the world develops dementia. Dementia is also the 7th leading cause of death globally.

Understanding the risk factors of dementia is thus paramount in tackling the disease. While different risk factors can influence each other and amplify the overall risk, calculating this synergistic risk is complex. So, the usual method is to assess the individual risk contributed by each factor separately rather than trying to calculate their combined effect.

As Bonhenry et al. explained, “Risk factors can interact, but the calculation of synergistic risk is complicated, so the standard approach is to present the marginal risk as partitioned between the individual causative factors.”

This article will do just that — to clarify how much of a risk infection poses in the development of neurodegenerative diseases like dementia, notwithstanding the importance of other well-known risk factors.

Infection as a risk factor

Before Covid-19, convincing evidence already exists for the interplay between infectious and neurodegenerative diseases.

For instance, Bonhenry et al. cited an insightful study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2021. This study pooled data across three large Finnish cohorts to examine whether someone who was hospitalized for an infection will be at an increased risk of dementia in the future.

Key insights from this study are as follows:

Previous hospitalization for any infectious disease increased the risk of dementia by 1.5-fold across three separate cohorts in Finland. This association was replicated with another cohort from the UK.

The risk of dementia remains high even after 10 years post-infection, showing that the negative effects of infections are long-term.

The risk of dementia is greatest for infections targeting the brain at a 3-fold increase. But non-brain infections were also associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of dementia, indicating that general inflammation may be sufficient to promote neurodegenerative diseases.

The risk of dementia is dose-dependent, with about 1.5–2-fold increased risk with one infection, 2.5–4.5-fold with two infections, and 2.5–7-fold with three or more infections compared to no infection.

Of course, there’re other studies that support the role of infection as a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases. I wrote about some of them in “The Viral Origin of Alzheimer’s Disease Remains Undecoded. But What We’ve Seen So Far Is Worrying” and “The Case for Virus Origin of Neurodegenerative Diseases Is Getting Stronger and More Important.”

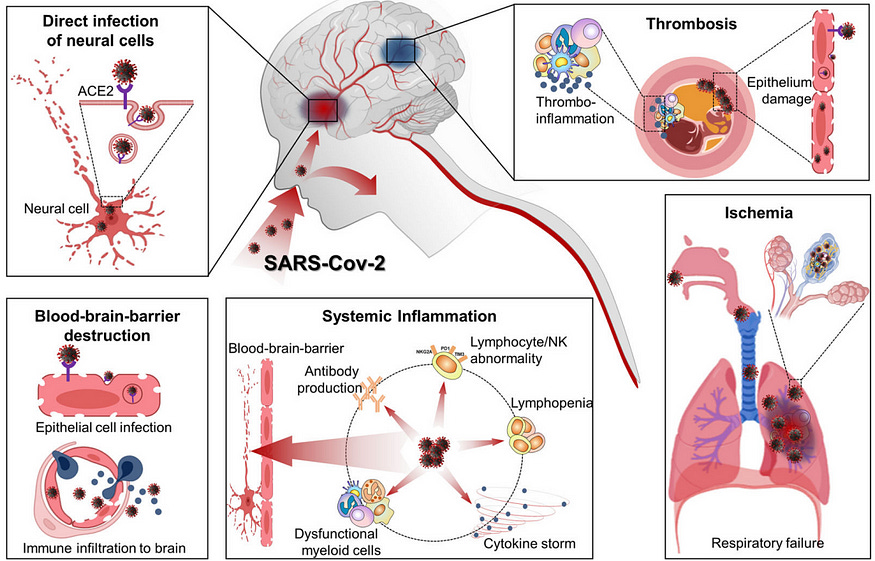

The crux of how infections can precipitate neurodegenerative diseases boils down to two main, widely accepted mechanisms (Figure 1):

Neuronal invasion: Certain pathogens can infiltrate the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier or propagating along the olfactory neurons into the brain’s olfactory bulb. As a result, brain cells may become infected, causing inflammation and neurodegeneration.

Systemic inflammation: Severe infections aggravate inflammation throughout the body, which can inflame the blood vessels and weaken the blood-brain barrier. Consequently, immune cells and inflammatory mediators may enter the brain, inducing neuroinflammation and the accumulation of neurotoxic proteins.

This problem is more relevant to chronic infections — pathogens capable of persisting in the body long-term. These include herpesviruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis virus, Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease bacterium), Treponema pallidum (syphilis bacterium), and, the most novel one, SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19 virus), all of which have been associated with neurodegenerative diseases in some way or another.

SARS-CoV-2 as a causative factor

In a more modern context, almost everyone has been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in the past few years. However, longitudinal data is still not yet available to decipher the long-term effects or risks of SARS-CoV-2 on the development of neurodegenerative diseases—many of which take decades to develop gradually and typically occur in those over 60 years.

Shorter-term data (≤2 years), however, are available, and Bonhenry et al. argued that they appear sufficient to argue for the causative role of SARS-CoV-2 in increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases, most notably Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD).

(AD is the most common form of dementia, i.e., loss of memory, while PD is characterized by loss of movement control. AD and PD represent the two most common types of neurodegenerative diseases worldwide.)

Here’s an overview of the available evidence to date:

Zarifkar et al. (2022) analyzed a cohort of ~3 million people covering half of Denmark’s population, of whom 0.9 million were tested for Covid-19. Results: Those who had Covid-19 (regardless of hospitalization status) had a 3.5-fold and 2.6-fold increased risk of AD and PD compared to those without Covid-19 at 12 months of follow-up.

Wang et al. (2022) analyzed a cohort of 6.2 million older adults in the U.S. Results: Those who had Covid-19 (regardless of hospitalization status) had a 1.7-fold increased risk of AD compared to those without Covid-19 within a year of Covid-19 diagnosis.

Rahmati et al. (2023) performed a meta-analysis of 12 studies — including the two studies above — covering >33 million people from various countries. Results: Those who had Covid-19 (regardless of hospitalization status) had a 1.5-, 1.7-, and 1.4-fold increased risks of AD, dementia, and PD, respectively, at up to 2 years of follow-up.

Additionally, Bonhenery et al. cautioned that SARS-CoV-2 is particularly damaging because it can damage blood vessels in the vascular system (Figure 1). This is because ACE2 — the receptor SARS-CoV-2 binds to — is highly expressed on endothelial cells of the blood vessels.

As a result, Covid-19 is known to come with vascular complications — such as thrombosis (blood clots), heart diseases, and stroke — in both the short-term and long-term (long Covid). Indeed, several studies have reported that Covid-19 raises the risk of stroke by about 2–3-fold. And stroke often leads to vascular dementia — a subtype of dementia also known as post-stroke dementia, although it’s less common than Alzheimer’s dementia.

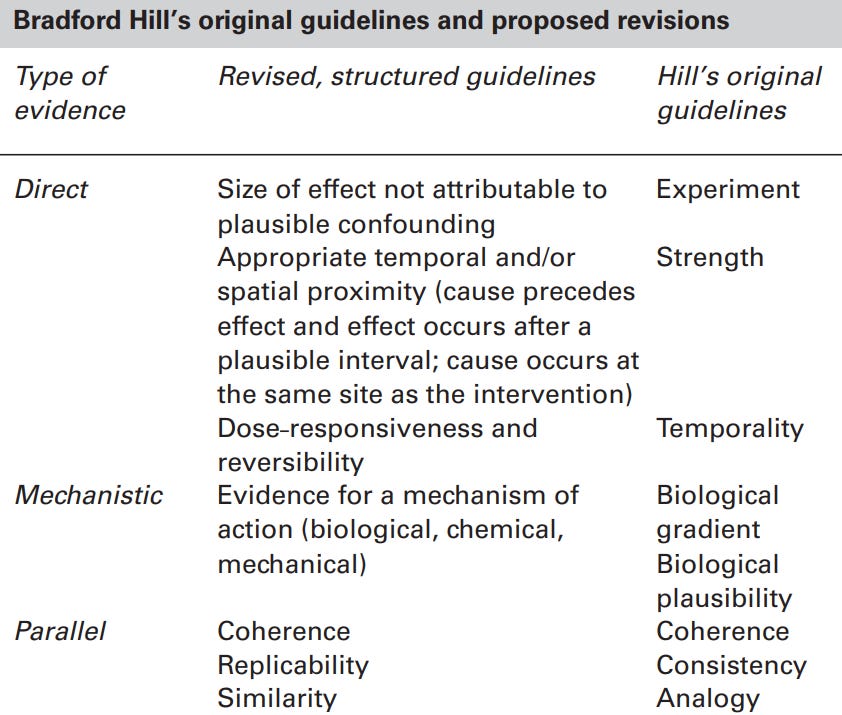

What’s interesting is that Bonhenry et al. applied the updated Bradford Hill criteria to determine cause-and-effect (Figure 2). Developed in 1965, such criteria help evaluate whether the observed association between an exposure (e.g., Covid-19) and outcome (e.g., dementia) is causative.

This approach is invaluable in observational studies, where establishing causality is complex. In clinical medicine, proving cause and effect requires randomized clinical trials, but these are often not feasible for certain research questions due to ethical concerns.

For example, the Bradford Hill criteria were pivotal in determining that smoking causes lung cancer, as it would be unethical to instruct participants to smoke in a clinical trial. Other instances involve confirming that air pollution is harmful, trans fat is not good for heart health, and human papillomavirus (HPV) can cause cervical cancer.

So, how does Covid-19 pass these criteria for causation?

Direct evidence: Multiple studies found that Covid-19 increases the risk of neurodegenerative diseases with a decent effect size (e.g., up to 3-fold) and within a reasonable timeframe (e.g., a year). Such association remains significant even after adjusting for confounding factors (e.g., sex, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and pre-existing diseases).

Mechanistic evidence: Multiple animal (in vivo) and cell culture (in vitro) studies have described biochemical pathways and mechanisms behind how SARS-CoV-2 could drive neurodegeneration.

Parallel evidence: Multiple studies from different research groups and countries have supported the direct and mechanistic evidence for the neurodegenerative capacity of Covid-19.

The broader context

As discussed above, the most consistent number seems to be a 1.5-fold increase in the risk of AD following Covid-19 (see Rahmati et al.’s meta-analysis). To put this into context, let’s clarify the lifetime risk of AD based on the most widely used numbers:

Men (65 years): The lifetime risk of AD is estimated at 6%, increasing to 10% for those over 65. A 1.5-fold increase would raise these risks to 9% and 15%, respectively.

Women (65 years): The lifetime risk of AD is estimated at 12%, increasing to 20% for those over 65. A 1.5-fold increase would raise these risks to 18% and 30%, respectively.

All Ages: The lifetime risk of AD is more challenging to estimate for all ages, as the disease typically affects older adults, but it’s likely around 1%. A 1.5-fold increase would then raise this risk to 1.5%.

(I focus on AD because it’s the most common form of dementia and the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease.)

But remember, synergistic risks are difficult to calculate. These numbers I presented are just estimates and will vary based on other risk factors, including genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

However, even though Covid-19 fulfils Bradford Hill’s criteria for causation, it remains difficult to identify the type of causation.

As Bonhenry et al. said, “Direct evidence should show appropriate temporal [time-related] sequence, which is contentious: it remains difficult to distinguish between the dementia cases hypothetically triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection and those merely accelerated by it.”

I think Covid-19 is predominantly an accelerator in those susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases. Otherwise, we would already see a huge spike in cases of neurodegenerative diseases if Covid-19 is mainly a trigger rather than an accelerator, which we’ve not seen in the 2024 annual report of Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures.

In my previous article, I highlighted that the million-dollar question is whether we will see a wave of neurodegenerative diseases post-pandemic, which is a difficult question to answer for now. This is more so when neurodegenerative diseases are typically age-related, and the Covid-19 pandemic has decreased life expectancy in numerous countries.

As such, both effects might even out with each other — Covid-19 robs people of their lifespan before age-related diseases can take root. But at the same time, neurodegenerative diseases like AD often take decades to form, so it might still be too early to see any long-term impacts.

That said, the present evidence outlined above argues for a solid case for include Covid-19 as a causative risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases.

“In light of this evidence, SARS-CoV-2 infection should be considered as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” Bonhenry et al. said, “even though the distinction between causation versus disease acceleration is not clear.”

This remains true despite the rapidly evolving Covid-19 variants. Bonhenry et al. acknowledged that while the severity of Covid-19 may vary between different viral strains, the rate of neurological outcomes following infection remains consistent. This is because neuroinflammatory damage is a fundamental aspect of the viral life cycle.

In the end, neurodegenerative diseases are multifactorial, with numerous risk factors that often act synergistically. And it’s time to recognize the importance of infections as one such risk factor. Then, we can dedicate more resources to exploring preventive factors like antiviral therapy or vaccines to curb the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

There’s actually strong, causative evidence that a herpesvirus vaccine reduces the risk of dementia. I covered this previously in “An Unexpected Ally In Dementia Prevention: Shingles Vaccination.”

If you have made it this far, thank you. If you enjoyed this, please subscribe below and share it with others. You can also tip me here. :))

There is no validated way of showing 'sars cov 2' infection- but yes people hospitalised with common symptoms of detox are more likely to be obese etc and more likely to develop AD.

Injecting animals with the contents of cell cultures, without doing adequate controls, is a cruel waste of time.

https://jowaller.substack.com/p/seeing-is-believing