Future of Covid: Will Schizophrenia Haunt the Next Generation?

A landmark study finds altered schizophrenia genes in Covid-positive pregnancies—and I asked the study author what it could mean for the next generation.

This article was originally published at Microbial Instincts on May 29, 2023.

Whenever I watch horror ghost movies, I always think the characters may have schizophrenia. If Covid-19 had occurred a generation or two earlier, I might have thought that the schizophrenia character‘s mother caught Covid during pregnancy.

This idea struck me when a commenter on my previous article shared a new study, showing that schizophrenia-specific genes are upregulated in pregnant mothers with Covid-19 vs. no Covid. This study isn’t to be taken lightly. It was published in a prestigious journal, Nature Communications, led by world-renowned scientists in the field of schizophrenia research.

A backdrop on schizophrenia

A patient affected with schizophrenia can’t differentiate between imagined thoughts from reality. As a result, they may believe in supernatural beings like ghosts. Schizophrenia is a mental disorder with symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, and other behavioral anomalies.

Schizophrenia typically occurs earlier in men (late adolescence to early twenties) than in women (late twenties). About 0.3–0.7% of the adult population has schizophrenia. Its risk factors include being male, pregnancy or birth complications, high parental age, early traumatic life events, and social isolation. But none of these factors fully explain or are specific to schizophrenia. Birth complications and early traumatic life events are also risk factors for borderline personality or anxiety disorders, for instance.

Thus, certain genetic predispositions likely interact with environmental risk factors to cause schizophrenia— the gene-environment multi-hit theory.

Indeed, further research has provided strong evidence for the causative genetic basis of schizophrenia. For instance, a Danish nationwide study in 2017 estimated that schizophrenia has a 79% heritability. A prior 2003 meta-analysis of 12 cohort studies put that number at 81%. These findings mean that genetic factors explain about 80% of schizophrenia cases.

In 2014, scientists from over 200 institutions published a breakthrough and the largest genetic study. Using a technique called genome-wide association study (GWAS), they pinpointed 128 genes significantly associated with schizophrenia, most of which were novel. Genes related to the glutamatergic system and synaptic plasticity in the brain were heavily implicated. This study was highly praised for advancing the genetic basis of schizophrenia.

GWAS is a research technique that screens the genomes of numerous people to find genetic variations that occur more frequently in those with the disease than those without. As genes are set from fertilization, they provide a strong basis for the origin of a disease or disorder.

Discovery of placental biology in schizophrenia

In 2018, a study leveraging the 2014 GWAS data discovered that placental genes also contribute to the causal role of schizophrenia, in addition to neuronal genes. The expression of schizophrenia-related placental genetic risks rose by up to 5 times in those with pregnancy/birth complications.

The placenta is a temporary organ that grows in the womb during pregnancy. It attaches to the womb linings and supplies nutrients and oxygen to the baby through the umbilical cord (Figure 1).

We thus attained an invaluable insight from the 2018 study — that neuronal and placental development interact with environmental stressors to influence the development of schizophrenia.

This innovative study was led by Daniel R. Weinberger, MD, a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University, Director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, and one of the pioneers of schizophrenia genetics research.

“The secret of the genetics of schizophrenia has been hiding in plain sight — the placenta, the critical organ in supporting prenatal development, launches the developmental trajectory of risk,” Weinberger said. “The commonly shared view on the causes of schizophrenia is that genetic and environmental risk factors play a role directly and only in the brain, but these latest results show that placenta health is also critical.”

In other words, what happens in the womb also plays a causal role in schizophrenia development, not just what happens in the brain. This is indeed a paradigm shift in how we view the pathology of schizophrenia, especially after decades of thinking it’s largely a brain disorder.

How Covid-19 affects placental biology in schizophrenia

Using a more advanced technique called transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS), a 2023 study by Ursini et al. of Weinberger’s team showed, for the first time, that schizophrenia-related placental genetic risks were magnified in Covid-19 pregnancies. Gianluca Ursini, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, is the study’s lead author and investigator, while Weinberger served as the senior author.

(TWAS combines GWAS with gene expression data to detect associations between genes and traits or disease. TWAS is, thus, more specific and informative than GWAS.)

Could this new study foreshadow an uncomfortable future of Covid-19 leaving a generational wave of schizophrenia? I’ll come back to this later. Let’s first understand the study findings.

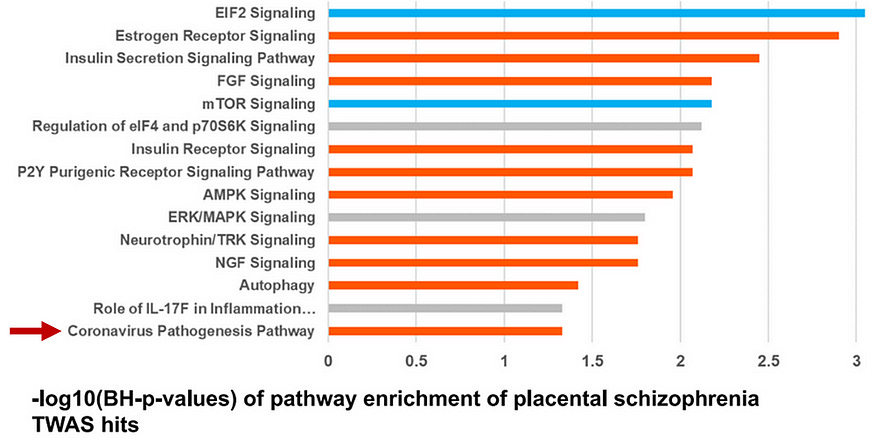

First, the paper identified altered activities of over 200 genes related to placental growth, protein synthesis, nutrient sensing, and trophoblast (placental cells that help the embryo attach to the womb) function in schizophrenia vs. non-schizophrenia samples. These genes were involved in EIF2, mTOR, estrogen, insulin, and cancer signaling pathways, as well as, surprisingly, coronavirus pathogenesis pathways (Figure 2).

Ursini et al. also detected over 500 schizophrenia-related genes in the brain of schizophrenia vs. non-schizophrenia samples, more than double the schizophrenia-related genes in the placenta. But when they computed the heritability of those genes, placental genes scored higher than brain genes.

“These data indicate that a sizeable proportion of the heritability of schizophrenia is explained by genetic variation associated with the expression of risk genes in placenta,” Gianluca Ursini, MD, Ph.D., the lead author of Weinberger’s team, wrote in their 2023 paper.

Ursini et al. took another step to show that these placental genes were specific to schizophrenia. They repeated their analyses with other developmental disorders such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and major depression. Placental risk genes were also detected in these developmental disorders, but to a much lesser extent than in schizophrenia, which indicates that most of the placental genes identified were specific to schizophrenia alone.

More worryingly, Ursini et al. found that these schizophrenia-specific placental genes were upregulated in Covid-positive than Covid-negative samples. These Covid-enhanced placental genes were ATF4, FURIN, IRF3, MAPK3, RPS10, and RPS17, which play roles in the regulation of cell survival, protein synthesis, and inflammatory responses.

These results support “the possibility that the immune reaction associated with this maternal infection may induce transcriptomic changes in placenta potentially relevant for schizophrenia risk,” Ursini et al. wrote.

Notably, placental risk genes for bipolar disorder and other developmental disorders were also enhanced in Covid-positive pregnancies, but to a much lesser magnitude than schizophrenia (Figure 3). This observation suggests that Covid-affected pregnancies bear more implications for future schizophrenia development than other developmental disorders.

Putting things in perspective

On top of advancing the importance of placental biology in the etiology of schizophrenia, Ursini et al. also shed light on the effects of Covid-positive pregnancies in influencing the placental biology of schizophrenia.

“One of the surprising results of the biological interpretation of the candidate placenta risk genes was activation of coronavirus pathogenesis,” Ursini et al. stated. “This led us to investigate expression of these genes in placenta from SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnancies. This analysis revealed upregulation of the set of schizophrenia-candidate causal genes in the coronavirus-positive cases, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy may be an environmental risk factor for schizophrenia.”

“More generally, the up-regulation of this gene set in placentae exposed to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection, arguably a potentially serious complication, further supports the possibility of a convergence between ELCs and genomic risk for schizophrenia,” the authors added.

Put simply, maternal infection with Covid-19 during pregnancy may represent an early life complication (ELC) for the fetus, with upregulation of specific placental risk genes for schizophrenia. This may correspond to a slighter higher risk of schizophrenia in later life.

But this theory is not without imperfections.

First, it’s only based on one high-quality study, which, although it has large sample sizes by the tens of thousands, has less than 10 placental samples from Covid-positive pregnancies. Still, the strong statistical association shouldn’t be a coincidence due to its very low p-values on the logarithmic scale. The authors also applied statistical tests to correct for possible coincidental findings that may arise from multiple comparisons.

Second, despite the causal nature of genes set from fertilization, GWAS and TWAS are association genomic studies that only suggest but do not prove causation. Only randomized controlled trials can prove causation, which is unethical as it entails us randomly infecting pregnant mothers with Covid and tracking their children’s development. So, only future observational cohort studies can tell if this generation’s Covid-positive pregnancies would lead to an increased risk of schizophrenia in later generations.

Third, the effect size is unclear, i.e., how much of a schizophrenia prevalence increase would Covid-positive pregnancies contribute to in the next generation? After all, the correlation between increased gene activity and increased risk in real life is not clear-cut.

I posed this question to Ursini himself, who was very kind in writing back to me constructively. We both suspect the absolute prevalence increase would be small. And here is my reasoning:

If 80% of schizophrenia cases have a genetic basis, then 0.24–0.56% of schizophrenia prevalence is attributable to genetics.

An increased risk relative to a rare risk would still be a rare risk. If the upregulated schizophrenia-specific placental genes contribute to, say, a 1.8-fold increased risk of schizophrenia, that would increase the schizophrenia prevalence to 0.43–1% — a noticeable but still low absolute prevalence.

But this calculation is an overestimate as it entails all pregnancies being Covid-positive. In the U.S., only 1.6% (6,380 out of 406,446) of pregnant mothers hospitalized for childbirth had Covid in 2020. Although this number discounted pregnant mothers before childbirth, it conveys the point that not all pregnancies are Covid-positive.

“I think that we may observe an increase in the incidence of schizophrenia and other neurodevelopmental disorders in the next generation,” Ursini responded to me, “but I also think that your assumption that your absolute risk will still be low is likely to be true.”

In fact, maternal infection during pregnancy is actually a risk factor for psychosis in later life. Schizophrenia is also a form of psychotic disorder.

For instance, Ursini directed me to a 2020 meta-analysis of 152 studies that investigated nearly a hundred predictive factors of psychosis. They identified parental age of <20 and >35 years, parental psychosis or other mental disorders, pregnancy/birth complications, and maternal infections, among others, as significant risk factors for offspring psychosis. The implicated maternal infections were Toxoplasma gondii, herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2), and other unspecified infections, which were associated with about 1.3-fold increased risk of schizophrenia (Figure 4).

A 2022 review paper also identified T. gondii and HSV-2 maternal infection as risk factors for offspring schizophrenia. This paper further cautioned that longitudinal monitoring of offspring schizophrenia risk is imperative for emerging infections like Zika- and Covid-positive pregnancies.

Ursini also referred me to a concerning 2022 study showing increased risks of neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., in motor function, language, speech, etc.) in one-year-old infants born to Covid-positive mothers.

All in all, like any other complex neurodevelopmental or mental disorder, there’s no single determining factor of the disorder. It’s often a range of factors involved. Ursini et al.’s study informed us that Covid-positive pregnancy is one such factor, at least for schizophrenia.

All that said, Ursini is very clear-headed, cautioning that “when we communicate these findings, we must always do our best to engage people to do all the possible to prevent [schizophrenia], without creating alarmism.”

“Schizophrenia is likely not a fate already defined at birth but rather the result of an altered trajectory of brain development that starts in utero and continues during childhood and adolescence,” Ursini added. “This trajectory could be recanalized.”

Ursini further informed me that their study could help point out early candidate biomarkers of schizophrenia risk, which scientists could use to detect genetic risk factors as early as in the growing fetal stages.

“If doctors knew which children were most at risk of developmental disorders, they could implement early interventions to ensure healthy brain development of the children, and to better follow who could be at risk,” Ursini shared with me. “All the events that happen during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, can contribute to preventing schizophrenia, so there is room for prevention!”

If you've made it this far, thank you for reading! Most of my Substack articles are paywalled, so if you found this valuable, consider subscribing for just $2.90/month (annual plan). Your support allows me to dedicate more time to researching and writing about lesser-known but important topics like this.