How a Single Study Proved the Cause of Multiple Sclerosis Is a Virus

It proved what we thought couldn’t be proved.

This article was originally published at Microbial Instincts on August 7, 2023.

In 1868, Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist at the Hôpital de Salpétrière in France, first coined the disease “la sclérose en plaques,” which means multiple sclerosis (MS) — to distinguish it from another type of movement disorder later known as Parkinson’s disease.

Though described in 1868, the cause of MS puzzled scientists for more than a century. This is until a 2022 breakthrough study finally enlightens us that the cause is, oddly, the seemingly innocent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a common childhood virus that causes typical fever and sore throat.

Let’s see how one study single-handedly proves what we thought couldn’t be proved; how one study truly deserves to be called a breakthrough; and how thorough and near-perfect science is done.

A backdrop on multiple sclerosis (MS)

(Feel free to skip this part if you are already familiar with this disease.)

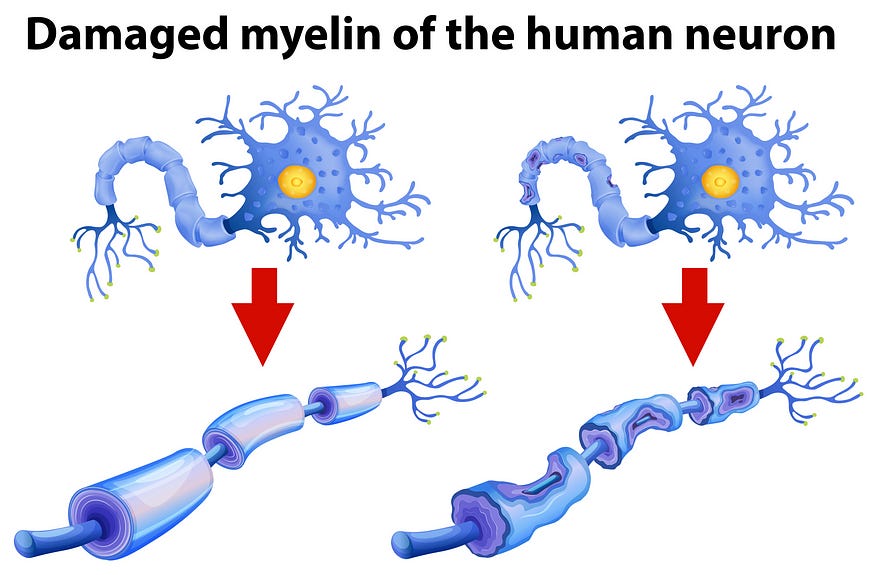

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disorder, where the myelin sheath (neuron’s insulator) breaks down (Figure 1). Such damage hinders neural transmission, causing chronic symptoms such as mobility issues, vision loss, muscle spasms and weakness, cognitive impairments, pain, speech and swallowing problems, and others.

But not all MS patients have these symptoms. In fact, an MS patient can have almost any neurological symptom, depending on the location and extent of myelin sheath damage, making MS a complex disease with no known cause or cure. Only anti-inflammatory therapies exist to temporarily curb MS symptoms.

MS is not at all rare. It affects about 2.8 million people globally, with an average prevalence of 35.9 cases per 100,000 people. Several factors can increase the risk of MS, which includes genetics and environmental factors like infections, smoking, and stress, among others.

Although a variety of infections (measles virus, human herpesvirus type 6, retroviruses, Chlamydia pneumonia bacterium, and even EBV) have been linked to MS, no smoking gun evidence has yet been established — that is until a breakthrough study was published in 2022.

The 2022 military study

The study was conducted by Bjorvenik et al. from the prestigious Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School, U.S.

Herein, they capitalized on the natural setting of the U.S. military, which enrolled over 10 million people from 1993 to 2013. At enlistment and every two years, the members undergo screening tests for infections. The remaining blood sera are then stored in the Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR), Maryland. By 2021, the DoDSR had already stored over 62 million samples, providing a wealth of resources for research.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a medically disqualifying condition in the military, so its diagnosis gets taken seriously. From 1993 to 2013, a total of 801 members developed MS during their military service. Each of them was then matched to two random controls — i.e., individuals without MS and of the same age, sex, race, and date of serum sample collection.

Using the stored sera to test for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) seropositivity (positive antibodies indicative of prior virus exposure), 800 out of the 801 members with MS had been exposed to EBV. So, the seroprevalence of EBV among MS patients stood at a staggering 99.9% in this study. For reference, EBV seroprevalence in the general population is only 60% to 90%.

To determine whether EBV exposure occurred before or after MS, Bjorvenik et al. tracked back the baseline statistics, where 35 MS patients and 107 controls were still EBV-negative. Results showed that:

Of the 35 MS patients, 34 actually tested positive for EBV before the onset of symptoms — a seroconversion rate of 97%. Put simply, EBV infection precedes MS about 97% of the time. The median time from the EBV seroconversion to MS onset was 7.5 years.

Of the 107 controls without MS, only 61 tested positive for EBV — a seroconversion rate of 57%.

So, the EBV seroconversion rate was higher for those who would later develop MS than those who wouldn’t. According to Bjorvenik et al.’s calculations, this means EBV-infected individuals were 32.4-fold more likely to develop MS.

To check whether their results are influenced by other behavioral or environmental confounding factors, Bjorvenik et al. repeated their analyses with cytomegalovirus (CMV). Akin to EBV, CMV is another type of common herpesvirus transmitted via saliva. However, unlike EBV, the CMV seroconversion rate occurred at a similar rate between those who would later develop MS and those who didn’t (Figure 2).

In epidemiology, a strong association can indicate cause-and-effect, provided other confounding factors are controlled for. For instance, smoking is associated with a 15–30-fold higher risk of lung cancer.

So, the 32.4-fold increased risk of MS from prior EBV infection can easily pass EBV as the causative agent of MS.

“Confounding by known factors is virtually ruled out by the strength of the association,” explained Bjorvenik et al. “To explain a 32-fold increase in MS risk, any confounder would have to confer a >60-fold increase in risk of EBV seroconversion and a >60-fold risk of MS.”

In fact, the next strongest risk factor for MS is a genetic one — i.e., HLA-DR15 allele homozygosity — which only contributes to a 3-fold increased risk. This genetic risk factor is also not associated with EBV infection and, thus, can’t explain the EBV-MS causal association.

“The existence of a still unknown factor that increases the risk of both EBV infection and MS by >60-fold is rather implausible and there are no good candidates, even hypothetical ones,” Bjorvenik et al. added.

Now, how might the seemingly innocent villain, EBV, trigger MS?

To this end, Bjorvenik et al. tested the serum levels of the neurofilament light chain (NfL), a disease biomarker of neurodegeneration. Increased NfL levels have been noted as early as 6 years before the onset of MS, making NfL a suitable biomarker of when the disease process began.

Bjorvenik et al. found no changes in NfL levels before EBV seroconversion in those who would later develop MS — indicating EBV infection occurred before symptom onset, as well as before the disease process of MS started. But after EBV infection, serum NfL levels began to rise to nearly 60%, and such an effect was absent after CMV infection (Figure 3).

To rule out the possibility it’s immune dysregulation that increases the susceptibility to EBV and MS, Bjorvenik et al. subjected the serum samples — collected shortly before and after the onset of MS — to a comprehensive screening using VirScan technology, which scans antibody responses against more than 200 viruses known to infect humans.

Results revealed that the overall antibody responses to viruses remain similar in MS patients and controls at both time points (i.e., shortly before and after MS) except for one virus that clearly stood out by a huge margin among the rest. Yes, it’s EBV (Figure 4).

This finding supports the specific role of EBV in MS development. If immune dysfunction or viruses, in general, were the main drivers, then the increased antibody responses wouldn’t be limited to EBV only.

By showing that EBV is specific to and precedes MS development, the study also ruled out the possibility of reverse causation — i.e., instead of a specific virus causing MS, it’s MS that caused increased susceptibility to viruses.

“Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that the occurrence of EBV infection, detectable by the elicited immune response, is a cause and not a consequence of MS,” Bjorvenik et al. concluded in their ingenious study.

More context

Why EBV? It’s counterintuitive that EBV, a common childhood virus that infects B-cells, can trigger a neurological disease. B-cells are the immune cells that produce and secrete antibodies.

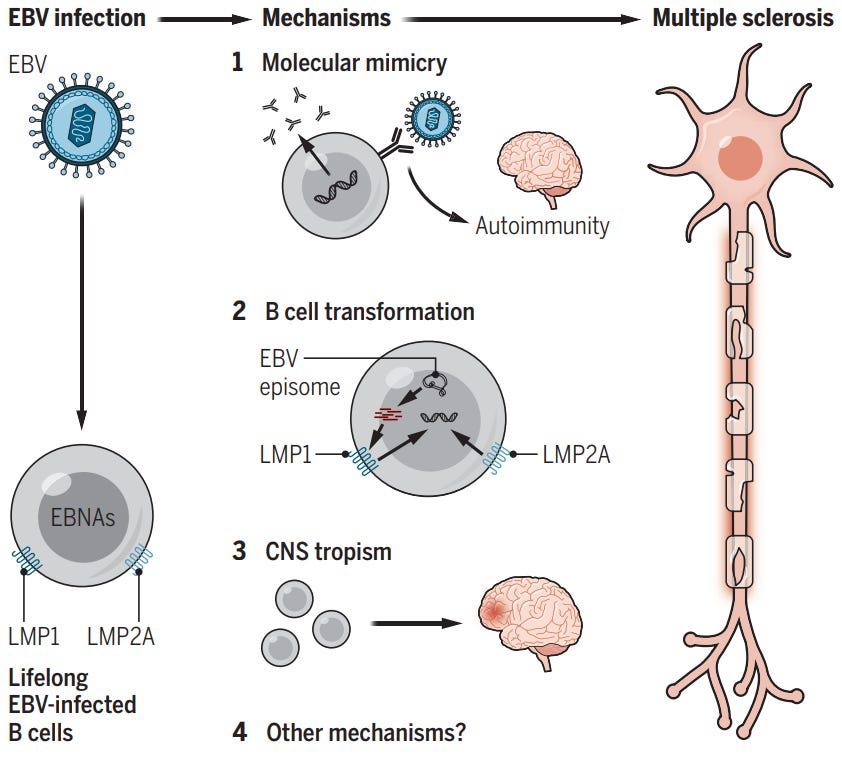

But in multiple sclerosis (MS), malfunctioning B-cells are attacking the myelin sheath of neurons for unclear reasons. Scientists have theorized that molecular mimicry might be at play, based on studies finding that certain EBV proteins share structural similarities to proteins of the myelin sheath or cells involved in neural transmission. As a result, antibodies targeting EBV proteins may cross-react with myelin sheath proteins.

Other theories of how EBV induces the pathogenesis of MS include (i) EBV-infected B-cells were abnormally transformed to attack the myelin sheath or (ii) EBV invading the blood-brain barrier and damages certain areas in the brain responsible for neural transmission (Figure 5).

If you remove B-cells from MS patients, their symptoms actually improve. In fact, B-cell depletion therapy with Ocrelizumab (i.e., anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies) is one of the most effective treatments for MS. Without B-cells, EBV has no cell host to replicate in.

Such observation suggests that EBV not only induces the disease process of MS but also contributes to the progression of MS. And that antivirals targeting EBV may be clinically beneficial for MS patients.

An EBV vaccine might even thwart the development of MS altogether. Although we have no approved EBV vaccines at present, due to multiple failed clinical trials in the past, new trials are underway.

One more thing to consider is that even though most of us have been exposed to or infected with EBV (seroprevalence of 60% to 90%), only a small minority develop MS. This indicates that other variables, especially genetic predisposition, are involved in MS development.

“Infection with EBV is likely to be necessary, but not sufficient, to trigger development of MS,” Stanford professors Robinson and Steinman explained it well in a perspective piece in Science. “Infection with EBV is the initial pathogenic step in MS, but additional fuses must be ignited for the full pathophysiology.” This is similar to a two-hit hypothesis — EBV and certain genetic factors — in deciding the fate of MS.

In the end, it only takes one ingenious, large longitudinal study to close the case that a prerequisite trigger of MS is the common childhood EBV infection. Who would have thought the origin of MS is a virus?

If you have made it this far, thank you. Subscribe to my email list below. You can also tip me here, and I will appreciate any financial support I can get.