Prenatal Infections Can Amplify Autism Risk (and Help Explain 1 in 7 Cases)

But research suggests that managing fever during pregnancy could make a difference in reducing that risk.

What if some of the seeds of autism were planted long before birth, triggered by a seemingly harmless prenatal infection? (Prenatal means before birth, during pregnancy.) Beyond genetic and other established risk factors, emerging research suggests that prenatal infections may silently rewire the developing fetal brain in ways that only become visible years later. This is the crux of what some are calling a new frontier in psychiatry—the fetal origins or the maternal immune activation hypothesis of psychiatric disorders.

A Brief Backdrop on Autism

Let’s start by clarifying what autism is. It exists on a spectrum, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is now recognized as a single diagnosis that encompasses what were once considered distinct conditions: classic autism, Asperger’s syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and the rare childhood disintegrative disorder.

While classic autism was historically seen as the most recognizable form—marked by language delays and social challenges—it may not be the most commonly diagnosed. In fact, milder variants like Asperger’s and PDD-NOS were more frequently diagnosed before the 2013 revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which consolidated these categories under ASD to reflect the continuum of severity.

But for ease of reading, I’ll use the term ‘autism’ instead of ASD in this article. (After all, I don’t think we say ‘ASD’ conversationally.)

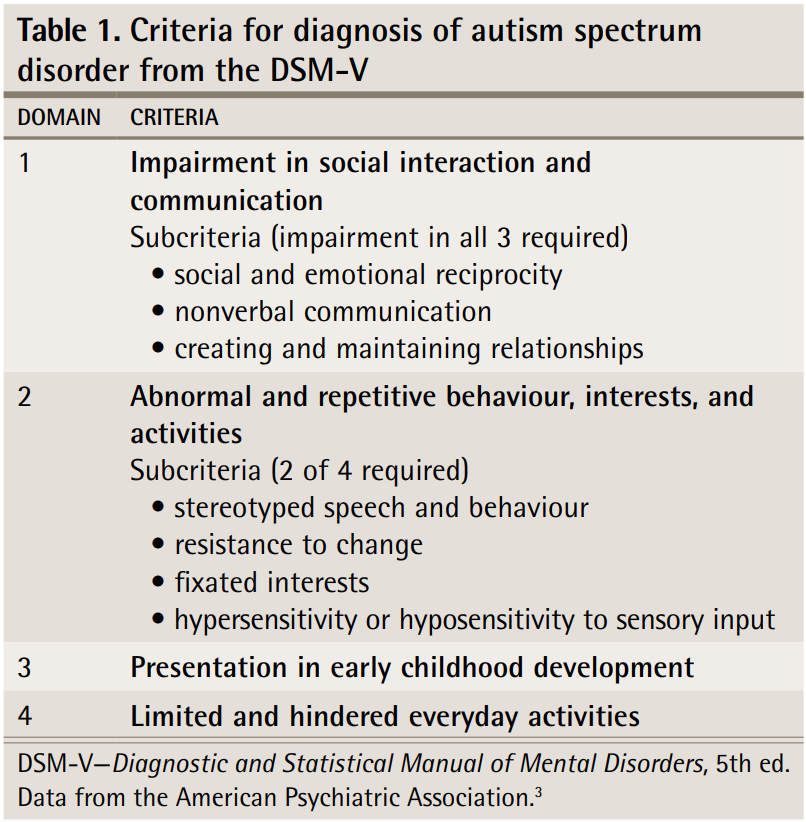

According to the DSM-5, autism is characterized by impaired social skills (3 out of 3 subcriteria required), as well as abnormal and repetitive behavior and interests (2 out of 4 subcriteria required). And these symptoms should appear in early childhood and affect daily activities (Figure 1).

The etiology of autism is multifactorial. A mix of genetic susceptibility, sex-related biology (autism is more common in boys than girls), womb conditions, and broader environmental factors is believed to tip the scale of who ultimately develops autism and who doesn’t. But the weight of each factor—and how they interact—is complex and not fully understood.

In this article, I’ll focus on one underappreciated piece of the puzzle: the womb immune environment, where maternal infection and inflammation may be shaping the developing fetal brain to increase the risk of autism.

What Population Studies Show

To investigate whether certain factors can increase the likelihood of developing autism, scientists turn to epidemiology, the study of patterns and determinants of a condition in a population. Essentially, epidemiology looks for trends in the population to identify associations between an exposure (e.g., infection) and outcome (e.g., autism). When multiple population studies investigate the same question, a meta-analysis can be used to combine the data and draw a more robust consensus or conclusion.

When applied to autism research, these epidemiological studies have found a consistent link between prenatal infections and a modest increase in autism risk. For example, the latest meta-analysis on this topic was done in 2021 by Teolico et al. from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York. In their paper, “Prenatal maternal infection and risk for autism in offspring: A meta-analysis,” as many as 36 population studies on the risk of autism following infections during pregnancy were synthesized.

“Analyses demonstrated a statistically significant association of maternal infection/fever with autism in offspring (OR = 1.32; 95% CI = 1.20–1.46),” Teolico et al. wrote. “The association does not vary much across the types of infections or when they occur during pregnancy.”

This means that children previously exposed to an infection in the womb during their mother’s pregnancy are about 32% more likely to develop autism (i.e., odds ratio, OR, of 1.32), with the risk ranging between 20% and 46% (i.e., 95% confidence interval, CI, of 1.20 to 1.46). This result is precise, with a narrow confidence interval, which indicates that the strength of this association is fairly certain and consistent; in other words, real.

Teolico et al. further conducted subgroup analyses to see whether the risk of autism varied depending on:

The type of maternal infection (i.e., bacterial, viral, or fungal; urinary, respiratory, or gastrointestinal).

The severity of maternal infection (i.e., with or without fever).

The timing of maternal infection (i.e., first, second, or third trimester).

Among these factors, only fever emerged as the most robust risk signal—children exposed to maternal fever in the womb had a 40% higher risk of autism compared to those whose mothers had infections without fever. In contrast, the effect sizes for infection type and timing did not reach statistical significance. So, inflammatory intensity plays a more decisive role in the risk of autism, rather than the infectious agent or timing.

Two previous meta-analyses in 2016 and 2017 also agree that prenatal infections are a risk factor for the future development of autism in the offspring. One of these meta-analyses reported that the autism risk is stronger when the mother was hospitalized for the infection.

Therefore, children exposed to infections in the womb face an increased risk of developing autism, particularly if the pregnant mother experienced a fever or required hospitalization during the infection.

It May Help Explain 1 in 7 Autism Cases

If prenatal infections play a causal role in fetal brain development (we will explore the biological causality in the next article), then they become a modifiable risk factor for autism.

According to Tioleco et al., if prenatal infections could be prevented or treated early and effectively, we may be able to prevent 12% to 17% of autism cases. This estimate is based on a concept called population attributable risk (PAR), which essentially asks: If we could remove this one risk factor from the population, how much disease could we prevent?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Infected Neuron to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.