Role of Mind-Altering Herpesviruses in Major Depression

Major depression is as much neurobiological as it is psychological. And certain viruses invade and disrupt neurobiological processes in the brain.

This article was originally published at Microbial Instincts on Dec 8, 2022.

As one of the leading causes of disability and suicide worldwide, major depression is arguably the worst disease you can get, for it crushes the soul, so to speak.

Major depression, clinically known as major depressive disorder (MDD), refers to depressive symptoms severe enough to impair daily activities. It’s different from sadness or loosely used depression as an expression of sadness. Various factors contribute to major depression, including lifestyle, genetic, and environmental factors. And our environment comprises viruses, some of which can invade the brain, causing neurological dysfunction that may underlie major depression.

In this article, I’ll describe four herpesviruses involved in major depression in the available literature to date. Herpesviruses are unique due to their ability to establish latency (dormant state) in certain cells in the body permanently once infected. Latent herpesviruses may then reactivate in later life to cause disease, especially under physical or psychological stress conditions.

Because most studies are of low quality, such as having low sample sizes and many unmeasured confounders, I’ll only describe studies of sufficient quality and relevance.

1. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV; human herpesvirus-3)

Over 90% of children have caught VZV, which may cause chickenpox (varicella) or no symptoms. Regardless, once infected, VZV enters latency in the peripheral sensory neurons for life and may reactivate decades later to cause shingles (zoster). But growing evidence shows that VZV reactivation poses more health consequences than just shingles.

In a 10-year longitudinal study in Taiwan, published in 2014, researchers randomly selected one million people from the population. After excluding those with a history of psychiatric disorder, the study identified 1,888 individuals diagnosed with herpes zoster, which were matched to 7,552 uninfected controls (randomly chosen). Random selection ensures that the sample is representative of the general population.

Results showed that individuals diagnosed with herpes zoster had a higher incidence of major depression (2.2% vs. 1.4%) or any depressive disorder (4.3% vs. 3.2%) compared to uninfected controls. Such differences were statistically significant, equating to increased risks of 49% and 32%, respectively, after accounting for potential confounders (e.g., age of diagnosis, sex, income, comorbidities, etc.)

The study authors believed that their findings may be explained by defective VZV immunity. Prior studies have reported lower VZV-specific T cell-mediated immunity in people with major depression than those without. (VZV is mainly controlled by T-cell immunity).

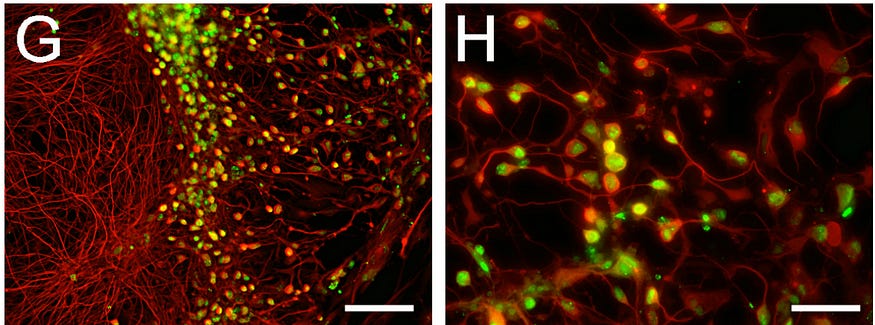

Poorly controlled VZV or shingles is known to damage nerve cells and cause postherpetic neuralgia, a type of chronic pain. In rare cases, encephalitis (brain inflammation) may even occur after shingles. In laboratory settings, VZV has been shown to infect neurons (Figure 1) and blood vessels in the brain, resulting in the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. So, it’s not far-fetched for multiple VZV reactivations throughout life to induce subclinical brain inflammation. And major depression is closely tied, in a causal manner, to brain neuroinflammation.

2. Epstein Barr virus (EBV; human herpesvirus-4)

Over 90% of the population worldwide has been infected with EBV at some point in their lives, especially during childhood, mainly via the oral route such as kissing and sharing eating utensils or food and drinks.

The first EBV infection can either cause a disease typical of common childhood illnesses or no disease. In either case, EBV will establish a latent state in B-cells in the body forever. In this state, EBV may occasionally reactivate and re-infect cells, which may or may not cause disease again. The disease EBV causes is infectious mononucleosis, with symptoms of fatigue, body aches, fever, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, or rash.

A 2021 nationwide study in Denmark tracked all 1,440,590 singletons who were born between 1977–2005 up to 2016. During this period, 12,510 of them had hospital contact for infectious mononucleosis. And these EBV-infected individuals had a 40% (45% in females and 28% in males) higher risk of major depression in later life compared to those uninfected, which remained statistically significant even after five years post-EBV.

These risk percentages were adjusted for age, sex, birthweight, maternal educational level, and other potential confounders, thus supporting EBV disease as an independent risk factor for major depression.

Although prior studies also found EBV to be related to major depression, they all had low sample sizes. A 2014 meta-analysis, for instance, calculated a 99% higher prevalence of EBV infection in people with major depression than in healthy people from a total of four studies, totaling only 221 depressed and 252 healthy cases (Figure 2).

So, the 2021 Danish study is the first large-scale study to deliver convincing evidence that prior EBV disease is a risk factor for major depression.

The mechanism by which EBV contributes to major depression is not known, but scientists suspect it’s immunological dysfunction. EBV is known to establish latency (dormant state) in B-cells and may reactivate periodically. EBV has also been found to prime B-cells to secrete auto-reactive antibodies that attack the neuronal myelin sheath, causing multiple sclerosis. But apparently, the defective myelin sheath is also a key pathophysiological aspect of major depression.

3. Cytomegalovirus (CMV; human herpesvirus-5)

About 80% of the general population has been infected with CMV. As a herpesvirus, CMV also stays latent in the body, specifically myeloid cells of the immune system, for life once infected, which may reactivate again to cause disease. In people with a normal immune system, CMV causes only mononucleosis (fever and rash). But in immunocompromised individuals, CMV can cause life-threatening end-organ dysfunction.

Recent evidence showed that CMV may be an independent risk factor for major depression too. In a 2017 longitudinal study spanning over 9 years, involving 771 elderly (60-101 years) Latinos, researchers found that those seropositive for CMV at baseline had a 38% increased risk of major depression in later life than those seronegative for CMV. And this risk was adjusted for potential confounders. When stratified by sex, the association between CMV seropositivity and major depression was only significant in women at a 70% increased risk, not men.

Such risk was absent in those seropositive for other infections (e.g., HSV-1, H. pylori, and T. gondii) compared to their seronegative counterparts at baseline, suggesting that the risk is specific to CMV.

Previous research has also produced similar findings. A 2018 study noted a trend toward higher CMV antibody levels in women with major depression. A trend means the association was nearly significant, but it’s not. An older 2014 study reported that high CMV antibody levels were associated with measures of poor mental health, including depression.

A 2021 study has shed light on how CMV may contribute to major depression. In this study of 99 participants with major depression, those seropositive for CMV showed reduced gray matter volume and neural connectivity in certain cortical regions in the brain, including regions involved in emotional regulation, compared to those seronegative for CMV. And this result was unaffected by age, sex, and other baseline variables.

The authors of this brain imaging study theorized that periodic CMV reactivations in the brain may damage brain tissues. Past studies have shown that CMV is capable of infecting cells of the blood-brain barrier, glial cells, and neurons in laboratory settings. As a result, CMV infection/reactivation has been observed to cause neuroinflammation and brain dysfunction in mice (Figure 3). And as much as major depression is a neurochemical brain disorder, it’s also an inflammatory one.

4. Human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6)

HHV-6 is universal. Nearly all of us have been exposed to HHV-6 in early life, typically via saliva from mother to child. Infected children usually show no symptoms, but some may develop sudden rash and fever. Once infected, HHV-6 enters latency in B-cells and T-cells, and it may reactivate in later life to cause encephalitis (brain inflammation) and opportunistic infections in immunocompromised individuals.

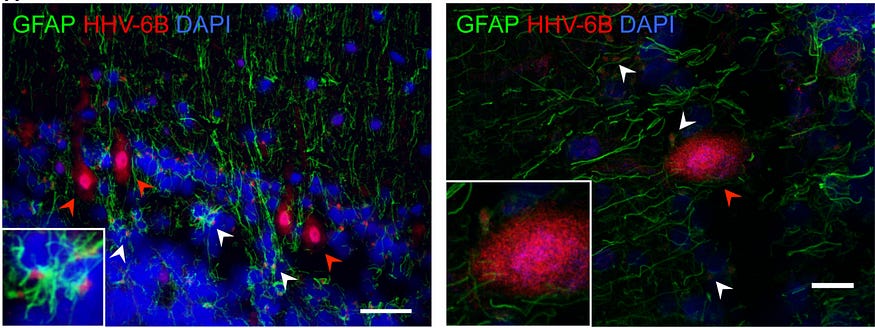

In a 2018 paper, researchers from Germany secured post-mortem brain samples from cases of schizophrenia, bipolar depression, and major depression, as well as cases without a history of psychiatric disorder. From these brain samples, HHV-6-specific DNA and late proteins* were detected in the brain cerebellum more frequently in bipolar (15 out of 49; 31%) and major depression (10 out of 15; 67%) cases than in non-psychiatric control cases (2 out of 50; 4%), but not schizophrenia (Figure 4). Such differences were statistically significant and not influenced by potential confounders such as the age of death, sex, smoking and alcohol use, etc.

*Late proteins indicate that the virus has been active (or reactivated) and manufacturing viral proteins.

But no longitudinal study has examined if HHV-6 reactivation increases the risk of major depression. While the 2018 paper found a higher prevalence of HHV-6 infection and reactivation in the brain cerebellum of patients with major/bipolar depression, it does not explain whether HHV-6 heightens the risk of depression, or depression heightens the risk of HHV-6 reactivation. That said, the former scenario seems likely, given that other human herpesviruses qualify as risk factors for major depression.

Viral etiology of major depression

Aside from herpesviruses, other viruses have also been associated with the occurrence or incidence of major depression, such as Borna disease virus 1, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1, human enterovirus, human papillomavirus, influenza virus, and even the Covid-19 virus, SARS-CoV-2. Although studies have also linked herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (herpesviruses 1 and 2) to major depression, the findings are inconsistent.

Major depression is thus unexplainable by a single virus agent, but rather by a combination of factors, including virus infections and reactivations, especially in those with less robust antiviral immune systems.

When pathogenic viruses invade the brain, some level of neurological dysfunction and neuroinflammation is likely to occur. If such dysfunction occurs in brain regions involved in emotional regulation and processing, major depression may likely develop. This is known as the microbial hypothesis of mental illness, pioneered by Jonathan Savitz, Ph.D., associate professor at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Tulsa, the U.S. But research on this research field remains scarce to this day.

Current technology cannot measure virus reactivations in the living brain. Only biopsies and autopsies can achieve that. So, we can’t tell if every occurrence of viral diseases —e.g., infectious mononucleosis from EBV, rashes from VZV or HHV-6, or shingles from CMV — means that the virus invaded the brain. To add another layer of complexity, having viruses in the brain does not necessarily mean they will cause harm, provided the immune system is robust and actively suppresses the virus.

In this way, ensuring a healthy immune system may be our best bet in not letting potentially depression-inducing viruses take over our minds. This also shows that major depression is as much biological as it is psychological and should be treated as such, without stigmatization.

If you have made it this far, thank you. Subscribe to my email list below. You can also tip me here, and I will appreciate any financial support I can get.