Shingles Vaccine Protects Against Dementia, But How Strong is the Effect? Here's My Attempt to Decode It

It could actually cut off almost half of all dementia cases in women.

Causal evidence is hard to come by.

It usually takes a randomized clinical trial (RCT) to demonstrate cause and effect, especially involving medical interventions. RCTs work because randomization evenly distributes the countless number of variables between individuals into the experimental and control groups, ensuring that the results seen are strictly due to the intervention.

But sometimes, we don’t need RCTs to demonstrate causality.

Sometimes, we can capitalize on existing systems to do so.

This is what three studies from the UK, the US, and Australia have done during the past year. They provide sufficient evidence to show in a causative manner that the shingles vaccine protects against dementia.

But the effect size exactly was unclear in these studies. After a deep dive and thought, here’s my attempt to pinpoint the effect size to infer insights on their real-world impact in the battle against dementia.

Study 1: Eyting et al. (2023), The U.K.

(I wrote about this study in “An Unexpected Ally In Dementia Prevention: Shingles Vaccination.” But I’ll describe it again with added details.)

Eyting et al. took advantage of a policy in Wales, U.K., which limited eligibility for Zostavax (i.e., a live-attenuated shingles vaccine) based on the date of birth. Individuals born before September 2, 1933, were ineligible for the vaccine, while those born on or after that date were eligible.

This setting provided a natural randomization. As Eyting et al. explained, “[Apart from] the probability of ever receiving the herpes zoster vaccine, there is no plausible reason why those born just one week prior to 2 September 1933 should differ systematically from those born one week later.”

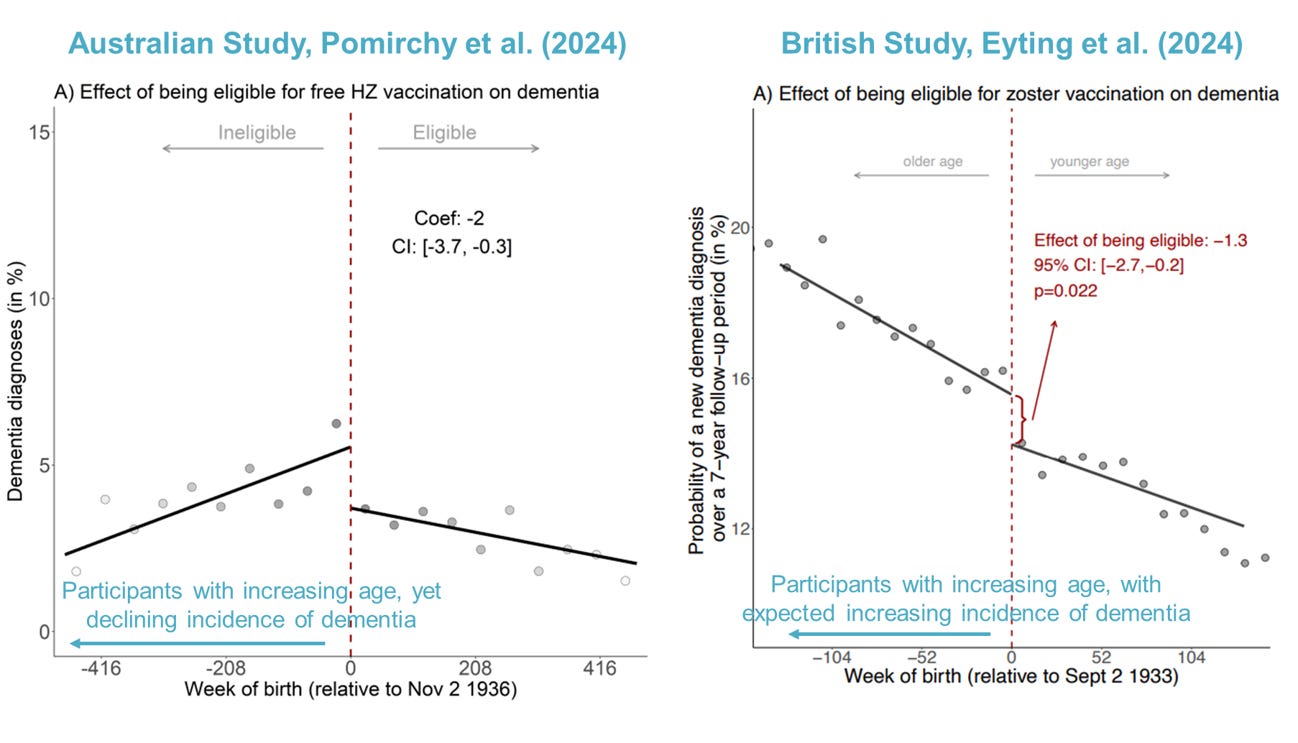

Eyting et al. followed over 280,000 participants (71-88 years old) between 2013 and 2021, comparing dementia incidence between vaccine-eligible and -ineligible groups. Results showed that, over 7.4 years, the incidence of dementia dropped by 1.3% in the eligible group from about 15.8% to 14.5%.

But this benefit was mainly seen and only significant among females, probably because dementia and shingles tend to affect females more often than males. Specifically, the absolute risk reduction was 2.9% among females eligible for Zostavax compared to ineligible females (Figure 1). Based on Figure 1’s rough guess (the precise number was not reported), the incidence of dementia dropped from 16% to 13% in vaccine-eligible females.

Importantly, Eyting et al. ruled out the possibility of healthy vaccinee bias, a confounding factor that’s almost impossible to control in typical observational studies. This bias occurs because vaccinated individuals tend to be more health-conscious and healthier overall.

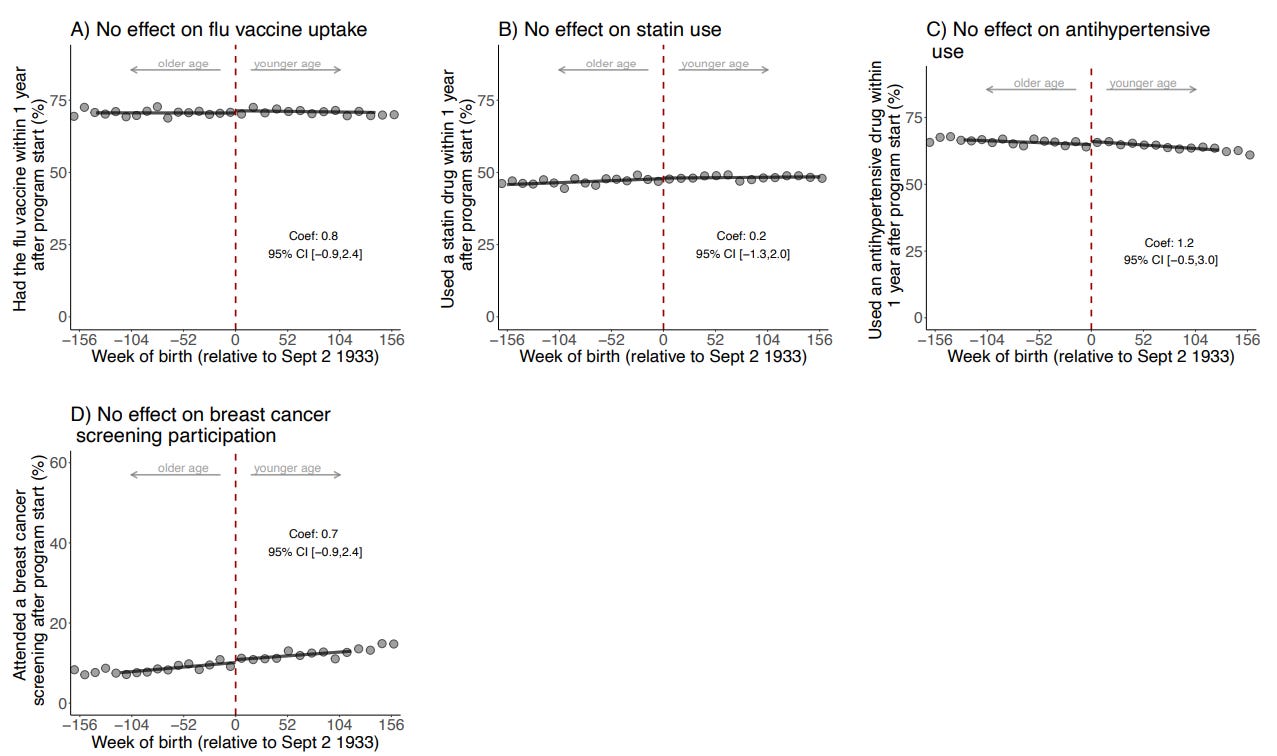

Eyting et al. mitigated this bias by showing that the vaccine-eligible group (i) only had reduced dementia occurrence and not other diseases and (ii) did not seek any more vaccines or healthcare utilization than the vaccine-ineligible group (Figures 2-3). If healthy vaccinee bias were present, a risk reduction in other diseases and more vaccine uptake would also be observed. And the absence of this bias indicates that the naturally randomized setting works in distributing health-seeking behavior equally between both groups.

All the evidence presented points towards Zostavax as the only explanation for the statistically significant reduction in dementia incidence among elderly women in this longitudinal study.

All that said, one caveat is that Eyting et al. only calculated the % reduction in dementia incidence in those eligible for Zostavax. But not everyone eligible went to get the vaccine. So, what’s the true effect of Zostavax then?

While Eyting et al. did not calculate this, we can estimate it by multiplying the incident reduction with the vaccine uptake proportion.

This works following the reasoning that the risk reduction was driven solely by those who were vaccinated in the eligible group. And this reasoning is valid because the study has conclusively established that the vaccine is the sole causative reason for the reduced dementia incidence.

Here’s the rough math based on the available info:

Being eligible increased the vaccine uptake to 47.2% and reduced the dementia incidence by 1.3% from about 15.8% to 14.5% in both sexes.

If the 1.3% incident reduction is driven by 47.2% of the vaccine-eligible population, then the incident reduction of dementia in those vaccinated would be 2.75% (i.e., 1.3*(100/47.2) = 2.75). This would cut the dementia incidence further from about 15.8% to 13.05% for both sexes.

But since the effects were not significant in men, let’s find the effect size in women using the same calculations:

Being vaccine-eligible increased the vaccine uptake to 43.7% (Figure 4) and reduced the dementia incidence by 3% from 16% to 13% in women.

If the 3% incident reduction is driven by 43.7% of the vaccine-eligible population, then the incident reduction of dementia in those vaccinated would be 6.86% (i.e., 3*(100/43.7) = 6.86). This would cut the dementia incidence further from 16% to 9.14%.

A 6.86% absolute reduction from 16% is very impressive — it practically cut off 42.9% of all dementia cases in women. Even if my rough calculations are off, the effect size is surely bigger than a 3% absolute reduction, given that only a little less than half of the eligible population got the vaccine.

Study 2: Pomirchy et al. (2024), Australia

Pomirchy et al., from the same research team as Eyting et al., also capitalized on the eligibility cutoff date for receiving Zostavax (live-attenuated shingles vaccine). But instead of prospectively following up with the participants like Eyting et al. did, Pomirchy et al. retrospectively analyzed existing healthcare records of over 100,000 patients in Australia.

(A retrospective study analyzes existing data to examine outcomes that have occurred, while a prospective study follows participants into the future, collecting data as events happen. Generally, prospective studies are more reliable; all RCTs are prospective. But retrospective studies can also provide decent data to support cause-and-effect relationships.)

In the Australian study, starting November 1, 2016, Zostavax was made free to individuals aged 70 to 79. Those who turned 80 just a few days before this date were ineligible, while those who turned 80 just after became eligible. This minor difference in birth dates provided a naturally randomized setting.

Using similar analyses as Eyting et al., Pomirchy et al. showed that vaccine-eligible individuals had a 2% points lower incidence of new dementia (from about 5% to 3%) compared to ineligible individuals over 7.4 years.† Unlike findings from the UK study, this Australian study noted no significant differences in the results when separated by sex.

Importantly, there were also no significant differences in the history of preventive healthcare services and chronic disease diagnoses between the vaccine-eligible and -ineligible groups (Figure 5). This provides strong evidence that the reduced dementia incidence can be attributed specifically to Zostavax and not to other health behaviors or conditions.

Now, what’s the effect size?

Following the same line of reasoning for this study:

Being eligible increased the vaccine uptake to 15.7% and reduced the dementia incidence by 2% from about 5% to 3%.

If the 2% incident reduction is driven by 15.7% of the vaccine-eligible population, then the incident reduction of dementia in those vaccinated would be 12.7% (i.e., 2*(100/15.7) = 12.7) — cutting the dementia incidence from about 5% to basically 0% (since it cannot be −7.7% incidence).

But it doesn’t make sense for only a 15.7% increase in vaccine uptake to reduce the dementia incidence from 5% to 3%. That’s a 40% relative reduction from not even one-sixth of the population.

(To better understand the difference between absolute vs. relative reduction, consider an intervention that reduced the incidence of x from 10% to 5%. The absolute reduction is 5%, while the relative reduction is 50%.)

This led me to conclude that the Australian study data is a bit flawed. I had my initial suspicion when I saw their main graph depicting the 2% absolute reduction in dementia incidence in those eligible. It’s suspicious that the dementia incidence didn’t increase with age in the vaccine-ineligible group (Figure 6). On the contrary, this pattern was obvious in the British study. Flawed data also makes sense, given that the Australian study analyzed data retrospectively, where things like missing or incorrect data are common.

Reading the discussion of Pomirchy et al. confirmed my suspicion.

“There likely was substantial underdiagnosis of dementia in our data. An estimated 8.4% of all Australians over the age of 65 are living with dementia, whereas only about 1.4% of patients in [our data] in the same age group in 2023 have been diagnosed with dementia….

Underreporting in our data was also the reason for which we refrained from scaling our effect estimates to the proportion of eligible patients who took up the vaccine. This would have allowed us to estimate the effect of actually receiving (as opposed to merely being eligible for) [the vaccine].”

However, Pomirchy et al. also defended that the underestimated incidence of dementia also applies to the vaccine-ineligible group:

“Assuming that the absolute degree of underdiagnosis of dementia did not differ across the November 2, 1936 threshold, then our absolute effect estimates remained unbiased but dementia underascertainment in our data would have led us to (potentially markedly) overestimate the relative effect size for the effect of HZ vaccination on dementia incidence.”

In other words, Pomirchy et al.’s study is not entirely useless. Its findings on the absolute 2% reduction in dementia incidence still hold, even though the reduction from 5% to 3% is most likely underestimated. The more likely scenario is that Zostavax would probably decrease the estimated national prevalence of dementia in Australia from about 8.4% to 6.4%.

Put simply, we cannot infer the relative reduction from this retrospective study. But it nevertheless substantiates the protective effects of Zostavax against dementia that was first demonstrated by Eyting et al.

Plus, the 2% absolute effect size in Pomirchy et al.’s Australian study is similar to the 3% absolute effect in the vaccine-eligible women in Eyting et al.’s British study. (Note this is before applying the math to estimate the effect size in eligible individuals who actually got the vaccine.)

Study 3: Taquet et al. (2024), The U.S.

Let’s proceed to the last study on this matter.

A different research team, Taquet et al., was intrigued by the earlier work of Eyting et al. and Pomirchy et al. on the causal protective effects of Zostavax, the live shingles vaccine, against dementia. But Zostavax is discontinued in the U.S. and other countries in favor of Shingrix, the recombinant shingles vaccine, due to its better safety profile and clinical efficacy.

Like the naturally randomized setting by birth dates in the U.K. and Australia, the transition from Zostavax to Shingrix after October 2017 in the U.S. was rapid enough to provide a similar naturally randomized setting too.

Taquet et al. also did their analyses retrospectively by matching 103,837 individuals who received their first shingles vaccine between November 2017 and October 2020 (the Shingrix period) to 103,837 individuals who received their first shingles vaccine between October 2014 and September 2017 (the Zostavax period). The mean age of both groups is 70 years.

Results: Those in the Shingrix period were at lower risk of dementia than those in the Zostavax period over the next 6 years — in a manner that translates “into 17% more time lived diagnosis-free or 164 additional diagnosis-free days among those affected.” The effect increased to 22% in vaccinated females, translating to 222 diagnosis-free days (Figure 7).

Both Shingrix and Zostavax were also more effective than influenza and Tdap (tetanus-diphtheria–pertussis) vaccines in the lengthening time lived without dementia. But I’ll not delve into the effect sizes of this since this analysis wasn’t conducted in a naturally randomized setting.

Similar to the studies by Eyting et al. and Pomirchy et al., Taquet et al.’s study also withstood multiple analyses designed to test the presence of any confounding factors, ensuring that the results observed in this naturally randomized setting provide near-perfect causal evidence.

While this study calculates vaccinated individuals directly rather than eligibility, it did not calculate the vaccine’s effect compared to unvaccinated individuals. This makes it hard to pinpoint the shingles vaccines’ true effect sizes since it compared two protective interventions.

But we can try:

Based on Eyting et al.’s study, we established a 6.86% absolute reduction in dementia incidence in Zostavax-vaccinated women (based on the reasoning that the 3% absolute effect size in vaccine-eligible women was solely driven by the 43.7% increased vaccine uptake).

If Shingrix confers a relative 22% higher effectiveness than Zostavax, we can increase the absolute effect size from 6.86% to 8.37% (i.e., 6.86 + 6.86*0.22 = 8.37). But one major flaw with this extrapolation is that Eyting et al. measured a reduction in incidence over 7 years while Taquet et al. measured a reduction in time lost over 6 years. Still, what I’m trying to convey with this rough math is that Shingrix would probably reduce dementia incidence by more than just 6.86% in vaccinated women.

By now, you may have noticed that time lost (or additional time lived without dementia) does not mean prevention. This appears true when looking at both sexes, where by the end of the 6-year follow-up, the dementia incidence in the Shingrix period caught up to Zostavax. But for females only, the dementia incidence in the Shingrix period remains lower than Zostavax (Figure 7), indicating that Shingrix continues to be more protective than Zostavax in reducing the incidence of dementia beyond the follow-up time.

What’s Next

Overall, these three studies argue for the causal role of the shingles vaccine (either Zostavax live-attenuated or Shingrix recombinant) in preventing — or at least delaying — the occurrence of dementia, especially in women.

The effect size is meaningful at about a 2-3% absolute decrease in dementia incidence just from being eligible for the vaccine. This effect size likely increases to about 6.86% and 8.37% for Zostavax and Shingrix for women who got the vaccine, reducing the incidence from 16% to 9.14% for Zostavax and to 7.63% for Shingrix. Please note that these estimates are for older women aged 70-80 years who are at high risk of dementia. After all, old age and female sex are some of the biggest risk factors for dementia.

One crucial point is that the incidences of other diseases don’t change in these studies on naturally randomized settings, which supports the cause-and-effect of Zostavax in protecting against dementia specifically.

If vaccines generally boost immune function, we would expect a decrease in the incidence of various other diseases, given that many diseases are influenced by the immune system. This suggests that the shingles vaccine has a distinct mechanism that specifically targets dementia.

But these three studies on natural randomization are not designed to decode mechanisms. So, we know that shingles vaccines protect against dementia, but we don’t exactly know how. In the next article, I will explore several hypotheses regarding this based on what we understand about shingles, herpesviruses, and dementia to get a better picture of what’s going on.